Liz Upton is the cofounder of one of the world’s most successful tech for good computer startups. Raspberry Pi is a credit card-sized computer that was originally designed to help children learn to code.

Since its launch in 2012, the robust and affordable device has sold over 60 million units and is now widely used beyond education, from industrial automation to environmental monitoring.

“It’s not just factories,” Upton quips. “At Heathrow Airport, those boards telling you when your plane’s leaving? Raspberry Pis. The scanners that read QR codes from your phone? Raspberry Pis too.”

As the first in of a series of ‘TechInspired’ interviews that shine a light on the different jobs that women are thriving at within the tech industry, we speak to Upton over video from a plush London hotel suite, just before she heads off to see Aida at the Royal Opera House.

“A million years ago, I used to be a singer,” she says. “I was a choral scholar at St Martin-in-the-Fields and an understudy at the Royal Opera House.”

And her journey from music to tech entrepreneurship is anything but typical.

Breaking into STEM

Upton describes her schooling at a strict Christian girls’ school as “terrible” and uninspiring when it came to STEM careers.

“It was very evangelical—we had bits of science books removed. My maths teacher used to call me ‘the half-caste,’ so I’d bunk off maths,” she recalls. “Everything I learned was from the library. I got my GCSEs but studied Law at university.”

Despite her lack of formal STEM education, Upton found immense satisfaction in Raspberry Pi’s mission to empower self-learners.

The idea for the Raspberry Pi was sparked when her husband, Eben Upton, noticed a decline in the quality and quantity of students applying for Computer Science at Cambridge, where he was director of studies at St John’s College.

“In the ‘80s and ‘90s, kids had programmable home computers like the ZX Spectrum and BBC Micro. By the 2010s, they had tablets, Xboxes, and smartphones—but nothing they could tinker with.”

Raspberry Pi in 2012: Model B was aimed at hardware developers and students

So, they set out to create an affordable, robust, programmable computer that kids could own and experiment with. But from the outset, Upton suspected it would find uses beyond education.

“Children have parents—some in engineering. A lot of those parents quickly took their kids’ Raspberry Pis into their workplaces.”

Building a community

As the former executive director of communications (a role that might be called ‘chief marketing officer’ today), Upton was instrumental in growing Raspberry Pi’s global community.

She documented every step of the prototyping process on the official blog, engaging hobbyists and industrial users alike.

Through her outreach, Raspberry Pi helped establish a network of about 300,000 young people worldwide attending weekly coding clubs. Upton took a hands-on approach, traveling extensively, attending ‘Raspberry Jams,’ and leveraging social media.

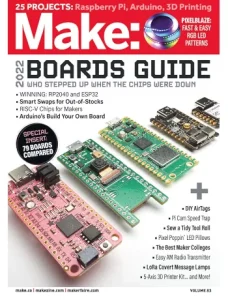

“Community building was much easier 10 or 15 years ago because of Twitter—back when it actually worked,” she notes. “We targeted DIY electronics enthusiasts through Make: Magazine and similar platforms, which were culturally dominant at the time.”

Building communities via user hubs like Make: Magazine were crucial in Raspberry Pi’s success

She also spent months traveling from US hackspace to hackspace, giving talks and demos to build awareness. By 2015, Raspberry Pi had become the biggest-selling home computer, later finding a major market in industry.

Financially the Uptons’ efforts have paid off: the commercial arm of the firm floated on the London Stock Exchange last March with a market cap of over £500m, with some reports stating that has surged to £1bn, achieving tech unicorn status.

However, it hasn’t always been plain sailing. The company faced major hurdles during the pandemic, particularly supply chain disruptions.

“It wasn’t just a chip shortage—it was across all components. A Raspberry Pi has more than 100 discrete parts, and if just one is out of stock, you can’t make the product,” she explains.

“We spent the whole pandemic on the phone begging for parts. It was awful.”

Still, Upton found time for a major life change: “I had a baby in May 2020. Don’t have a baby in a pandemic—it’s not very social!”

Empowering women in tech

One of Raspberry Pi’s proudest legacies, Upton says, is the number of women-led businesses it has inspired. She highlights Limor Fried (aka Lady Ada), founder of Adafruit Industries, which builds and sells Raspberry Pi-based products.

“She’s a phenomenal engineer, and it’s brilliant to see more women coming through the pipeline,” Upton says. “We’re finally seeing the results—more young women in universities and in tech careers.”

Engineer and entrepreneur Limor Fried builds and sells Raspberry Pi based products

Asked what advice she’d give to women starting out or transitioning into tech, Upton is direct: “Don’t try to behave like a man,” she says.

“You see a lot of that,” she adds. “Management styles are interesting. I’ve noticed that successful women tend to lead differently. I wouldn’t call it ‘softer,’ but there’s often a more personal approach that builds stronger relationships with their teams.”

Upton also believes the industry needs to be more open about financial incentives. “We’re so shy about talking about money, and it holds people—especially women—back.”

HR leader explains how her firm is turning fries into miles

She notes that, in her experience, women are less likely to negotiate salaries or promotions.

“When I was hiring, I noticed that men would apply for roles even if they didn’t meet all the criteria. But a woman once told me she held back from applying for a management position because she didn’t tick every box. I had over 100 male applicants, none of whom met every requirement either.”

From Aida to tech diva: Raspberry Pi’s Liz Upton

That realisation led Upton to rethink her hiring practices, ensuring they account for how differently men and women approach job applications and negotiations.

And as for her own financial standing?

“I’m a millionaire, not a billionaire,” she says with a laugh. “Half of Raspberry Pi’s IPO shares went to the Foundation, and we made sure every employee received stock options.

“We could have enriched ourselves more, but at some point, money just becomes silly. And look at me—I’m sitting here in a very nice hotel!”

Beyond gender, Raspberry Pi’s nonprofit arm also works with other underrepresented groups, including disadvantaged white boys on free school meals, “who are still the least likely to achieve social mobility.”

While Upton has now moved on from Raspberry Pi, she continues to support startups through her venture firm, Negroni Business Studios, which focuses on scaling businesses run by underserved founders.

BOW: Democratising Robotics

As well as Negroni Ventures, Upton was headhunted late last year to become the chair of global robotics software company BOW.

BOW—short for “Bettering Our Worlds”—aims to make it possible for any software developer to create, deploy, and manage robotics applications.

BOW selected her: Upton’s now working with the guys at the robotics software development platform

“They’re democratising robotics in a similar way to how Raspberry Pi democratised computing,” says Upton.

Currently, programming multiple robots in a shared environment requires individual coding for each device. “They’re not going to have the same firmware,” she explains.

“BOW provides middleware that’s platform- and language-agnostic, allowing developers to program any robot in its dataset in any language.”

She hopes Bow will disrupt robotics programming and make it more accessible to businesses and individuals alike.

“It’s a tough field to get into. Some of the programming languages used in robotics are less common, and there are only around 150,000 specialist roboticists worldwide,” she says.

“Some incumbents like keeping barriers to entry high. We saw that with Raspberry Pi too—people like being the only ones who know how to do something. But I don’t think the world should work that way. And so, here we are.”

TechInspired’s key takeaways:

- Different paths can lead to tech. Upton’s journey from law and music proves you don’t need a traditional STEM background to succeed.

- Building communities is powerful. Raspberry Pi’s success was fuelled by grassroots engagement and genuine user passion.

- Women need to negotiate more. Don’t undervalue yourself—apply for jobs and discuss salary with confidence

- Tech can be a force for good. Raspberry Pi’s impact goes beyond profit, supporting education and social mobility.